Master filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki steps out of retirement to bring us ‘The Boy and the Heron’, arguably one of his most personal, emotional and wonderfully surreal films ever.

“Animators can only draw from their own experiences of pain and shock and emotion”. That quote from Miyazaki, could be the tagline for The Boy and the Heron, his 12th film for Studio Ghibli which was founded in 1985. The legendary director left filmmaking after his 2013 film ‘The Wind Rises’, only to dabble with a short film several years later, which sparked an idea for this new feature in 2016.

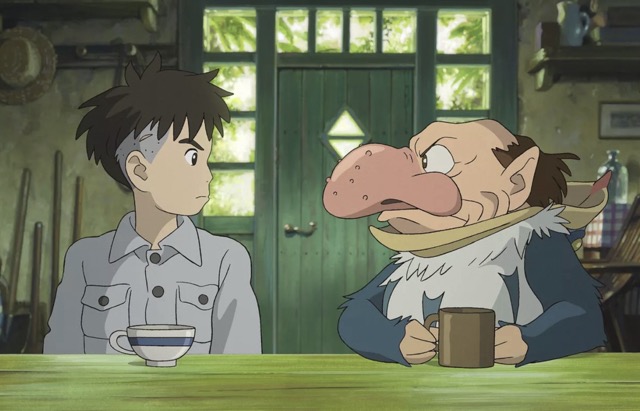

Set during the Second World War, The Boy and the Heron tells the tale of Mahito (Luca Padovan), a Japanese boy, who after the death of his mother in a hospital fire, must move to the country with his father and his new pregnant stepmother (Gemma Chan). The early flashback scenes of the fire are some of the most emotionally evocative in the film. Miyazaki’s experiences of World War II as a boy have shaped much of his work, and you can feel the fear and confusion of the fires and panic through the breathtaking impressionistic animation in those moments. Upon arriving at the new house, not all is as it seems as a mysterious grey Heron seems to be stalking Mahito, trying to draw him closer to a strange tower on the house grounds. Distracted by the Heron, Mahito becomes closed off and distant, needing to discover the truth about the Heron. The film’s Japanese title ‘How Do You Live’, is taken from the 1937 novel of the same name by Genzaburo Yoshino. The film isn’t a direct adaptation of the book, but shares some of the same themes of spiritual growth and humanity. However there is a moment in the the film where the book is gifted to Mahito by his late mother.

In Japan, the film wasn’t promoted at all except for a simple poster. Yet this didn’t stop the film from being incredibly popular, just showing what the return of Miyazaki and word of mouth can do. In the West we of course got a trailer, the tone of which lures you into thinking this may be an easier watch than it really is, with the fantasy-led visuals leading you to believe this may be in the same vein as more digestible Ghibli films like ‘Spirted Away’ or ‘My Neighbour Totoro’. Both of which have fantastical elements but are ultimately driven by child-like whimsy or the archetypal ‘Heroes Journey’. The Boy and the Heron however is far more contemplative, closer in tone to ‘The Wind Rises’. Mahito’s father (Cristian Bale making a return to Ghibli) even works in aircraft production and development, which was the job of the main protagonist in The Wind Rises and a passion of Miyazaki’s.

At it’s base level the film is almost a dark retelling of ‘The Wizard of Oz’, but with deeper musings on life and death. That may sound too heavy and there are points of real darkness throughout, yet the film is also a true adventure story. Much of what I feel is missing from cinema meant for all ages these days is a sense that moments CAN be dark and disturbing. All too often, filmmakers and studios seem afraid to explore more complex themes in films that are marketed as ‘family movies’ for the sake of a box office return. Films that ‘disturbed’ me as a child (Return to Oz springs to mind with its similar themes) can now be viewed as an adult as richer and more rewarding, and I hope that’s how this films finds new audiences as time goes by.

The mystery slowly unfolds for the first hour or so of the film, Mahito’s frustration deepening as he attempts to find out about the Heron and the mysterious tower, the origin of which we later find out is something not of this world. At one point, Mahito believes he’s seen his stepmother wander into the forest, giving him motivation to conquer his fear and finally be brought into the fantastical world by the Heron. This is when the film really steers into the strange as we’re introduced to a place where the living and the dead exist simultaneously. Here the Heron itself takes on another strange form and is given a voice and purpose alongside Mahito as a guide through the strange landscape. The character (fantastically voiced by Robert Pattinson) even provides some of the more welcome comedic moments that punctuate the heavier beats of the film.

Something that’s always struck me about Miyazaki’s work is the dream-like nature of the worlds he builds, even in his gentler and more literal outings, I always have an intriguing sense of uneasy familiarity. That sense has never been stronger with this film with the beautifully melancholy journey Mahito goes on. It’s similar to the way we experience dreams, in which what is happening always feels involved, but then you’re suddenly somewhere entirely different before you can dwell too much on what just happened.

Along the way, Mahito meets various characters, like a fire maiden whom we first encounter as she helps protect possibly the cutest character’s Miyazaki has ever created, the Watawata, from a flock of hungry pelicans. These tiny, soon to be plush toy balloon-like creatures, represent the souls of babies yet to be born back on Earth. Mahito is also aided by the younger version of Kiriko (Florence Pugh) one of the seven old maids (who share some seven dwarf-like qualities that work back at the country house), who is also sucked into the afterworld at the same time.

One of the threads that guides you through this world, along with occasional dips back into the ‘real world’ as Mahito’s family attempt to look for him, is the amazing score by Joe Hisaishi. His music is intrinsically linked to Miyazaki’s work, much in the same way John Williams has been an essential part of Spielberg’s work over the decades.

The film’s third act is puzzling, as it is somehow urgent and anti-climactic at the same time. What follows are some baffling additions to this already bird-heavy world, in the form of giant anthropomorphic parakeets (I know) that aim to stop Mahito, but offer little in the way of dramatic tension as they’re introduced so late in the film. The mysterious creator of this afterworld, the builder of the tower, is a God-like keeper of ‘the balance’. However his time is growing short, his world is becoming unstable and in now looking for a replacement in Mahito, who is his descendant. Without spoiling the end, it’s a typical Miyazaki ending/resolution that is emotionally pleasing, if not wholly satisfactory from a narrative sense… but maybe that’s the point? The narrative idiosyncrasies could put off newcomers to studio Ghibli, but really the only lend further to the fantastical qualities of the film.

After ruminating on the film for a few days, I believe this is where film is meant to exist… in a far more emotional place, than a logical one. With Miyazaki himself admitting that he often starts a film, or even begins storyboarding it before he has the full plot, citing the process to be more spiritual than technical. It’s not meant to be strictly linear, it is instead the deeply introspective work of an ageing director who is not only unafraid to let his imagination run wild, but hopes you’ll place a trust in him to see you through. It’s certainly some of the most beautiful work the studio has ever produced and at 82 years of age, could conceivably be the last work of Miyazaki’s we see released in a traditional sense. If that were to be the case, it would be a fitting end to a career spent pushing animation and filmmaking to new heights that make Miyaki inimitable as an artist.

Author: Arron Dennis